The scene is the 2011 NFL Draft.

The team is the Atlanta Falcons.

Fresh off a loss in the Divisional Round at the hands of Aaron Rodgers and the eventual Super Bowl champion Packers, Falcons GM (and now SumerSports CEO) Thomas Dimitroff felt he had to make a bold decision. While his former boss and future Hall of Famer, Bill Belichick, tried to dissuade him from moving up into the upper echelons of the draft to acquire a playmaker (as chronicled in the wonderful book War Room by Michael Holley), Dimitroff felt that a blue-chip talent was what the Falcons needed to get over the top.

The Dirty Birds had Roddy White, who led the NFL with 115 catches in 2010, and Hall of Fame tight end Tony Gonzalez, whose 656 yards was second on the team that year. Only one other player (Michael Jenkins) had over 500 yards receiving. Dimitroff coveted a deep threat that could do what the Eagles’ DeSean Jackson could do, which was better open the middle of the field for White and Gonzalez and set up his offense for the future with a potential number one receiver when White retired.

Dimitroff made a trade with the Cleveland Browns to move up to the sixth pick of the draft to select Alabama’s Julio Jones, a 6’3’’, 220lb wide receiver with sub-4.4 speed and great college production. He wasn’t a perfect prospect, as Dimitroff and Falcons owner Arthur Blank sat and watched former Raiders and Bucs head coach Jon Gruden go over Jones’ drops while with the Crimson Tide on ESPN’s broadcast. Belichick infamously told Dimitroff that Jonathan Baldwin, who the Chiefs selected later in the round and who would play three years in the league, amassing fewer than 700 yards receiving and just two touchdowns, was just as good as Jones.

The real sticking point in the minds of many analysts, though, was over price. Dimitroff surrendered his first rounder in 2011 and his first rounder in 2012, along with a second and fourth-round pick in 2011 and a fourth rounder in 2012. Every draft chart, even the Jimmy Johnson draft chart that many believe overvalues high-end picks, said that it was an overpay and that it was a long shot that the player Dimitroff acquired would be more valuable than the sum of the players that would be drafted with the picks he gave up.

Here’s the trade charts for that trade!! pic.twitter.com/wXVjAqsIwg

— Joseph Hefner (@josephjefe) April 3, 2024

As most know by now, Dimitroff and Jones got the last laugh, with Jones earning seven Pro Bowls and five All-Pro berths with the Falcons while generating a 55% success rate on his targets, which is higher even than the 50% success rate from A.J. Green, who was drafted two spots ahead of him (per Pro Football Reference (PREF)). The Browns, on the other hand, did very little (pun intended) with the picks they received from the Falcons, including using one of the picks to move up to select Trent Richardson the following year before trading him to the Colts the next fall.

Now, a sample size of one doesn’t necessarily render the trade charts wrong in any way, shape, or form, and while I think luck is a first-order term in football (and sports in general), I think it’s an even worse teacher. But I also think treating residuals entirely as noise is misguided, and many of the insights we gain from research are from exploring possible mechanisms for the residuals between model predictions and results.

One that I have been exploring of late is the idea of selection bias in these draft trade charts. This stemmed from discussions with Ryan Brill and Adi Wyner of Penn, who in recent research about EPA and win probability pointed out that modern EPA models have some bias due to the fact that teams that are in the red zone more frequently, for example, are different (likely better) than teams that aren’t, and hence estimates of expected points will likely be biased upward.

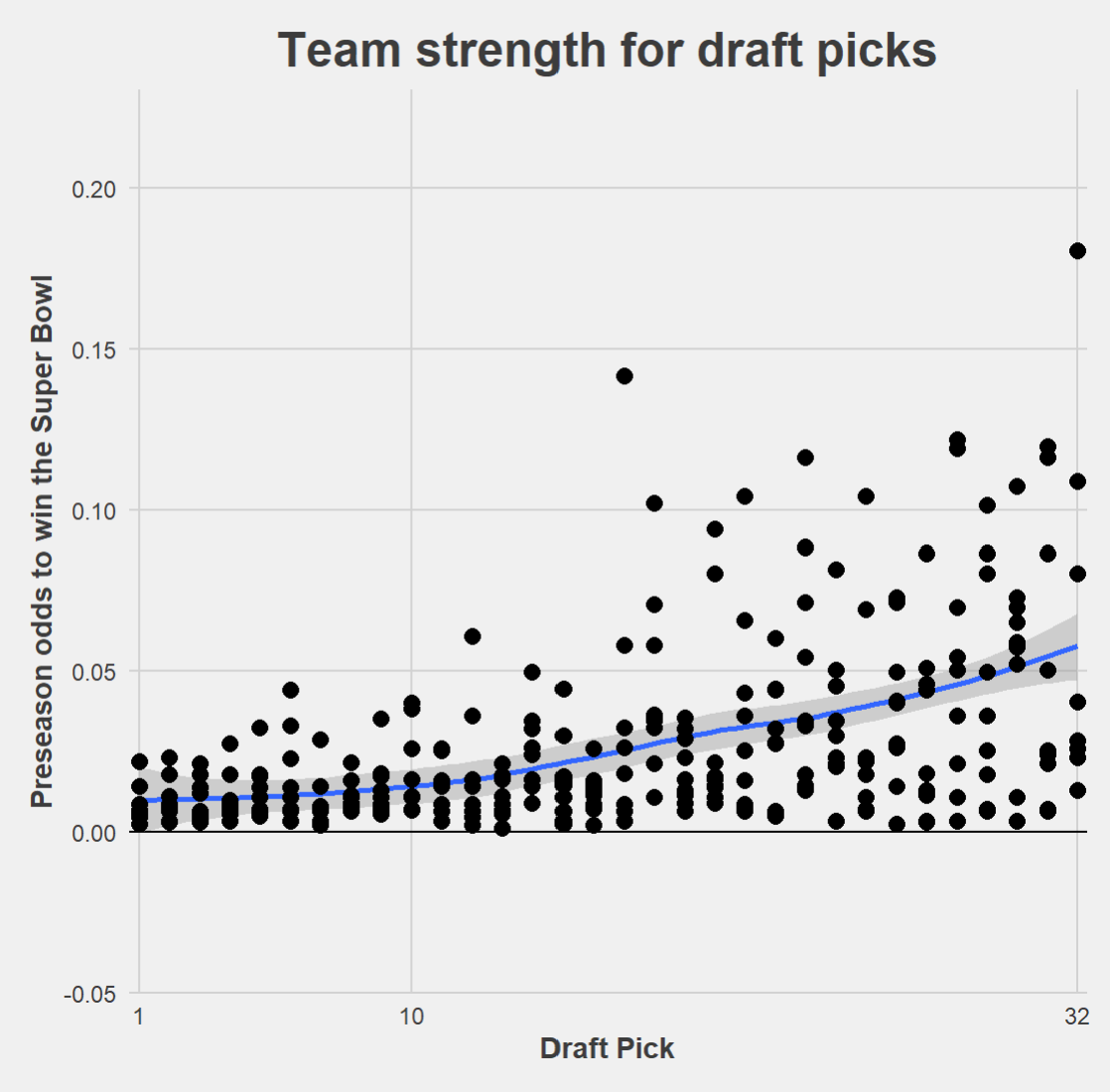

There is likely a similar problem in the NFL draft. Teams with less talent pick at the top of each round on average and teams with more talent pick at the bottom of the round. For example, here are the vig-free championship odds (per PREF) for the drafting team per pick slot for the 2011-2019 drafts (we’ll talk about why I used that year range in a second).

Curious about this, I took the code from Ben Baldwin’s yearly (and awesome) overview of the current state of NFL draft curves, which takes the approach of Jason Fitzgerald of OvertheCap, and Brad Spielberger, formerly of OverTheCap and PFF and now of Grand Central Sports Management (congrats Brad!). The model uses APY, as a percentage of the salary cap, of the player’s second contract after their rookie deal as a proxy for the value of the draft pick (there are some issues with this approach, and every approach, which is why you should try to replicate this with your draft curve, too). They use data from 2011 to 2019, as the 2011 CBA is largely the law of the land in the NFL, and the 2019 draft class is the latest to have every player have a second-contract decision. While Baldwin used a LOESS curve, with percentage APY of cap as the response and draft selection as the predictor, over the whole draft (256 picks), I’m going to restrict my data over just first-round picks, which in most years is just picks 1-32.

I first fit a LOESS curve to first-round picks based on the odds for the team picking in that slot to win the Super Bowl that year. That’s the blue line you see in the plot above and is the pick’s expected Super Bowl odds. Then, for each actual draft pick, we took the team’s odds to win the Super Bowl, subtracted the expected Super Bowl odds, and then divided by the expected Super Bowl odds of the pick. In essence, this measured how much more or less likely to win the Super Bowl, in relative terms, was the team picking at that pick than the average team that has picked there from 2011-2019.

Adding this feature to the model in Baldwin’s article, applied to only first-round picks, did improve model diagnostics when predicting second-contract APY as a percentage of the cap, even though our measure of team strength (that season’s Super Bowl odds) were admittedly blunt. It also improved model diagnostics when added to a model that predicted second contract APY as a percentage of the cap for all drafted players, including quarterbacks (Baldwin’s work did not include quarterbacks).

Thus, there is statistical evidence that the value of the draft pick is affected by the strength of the club using the pick.

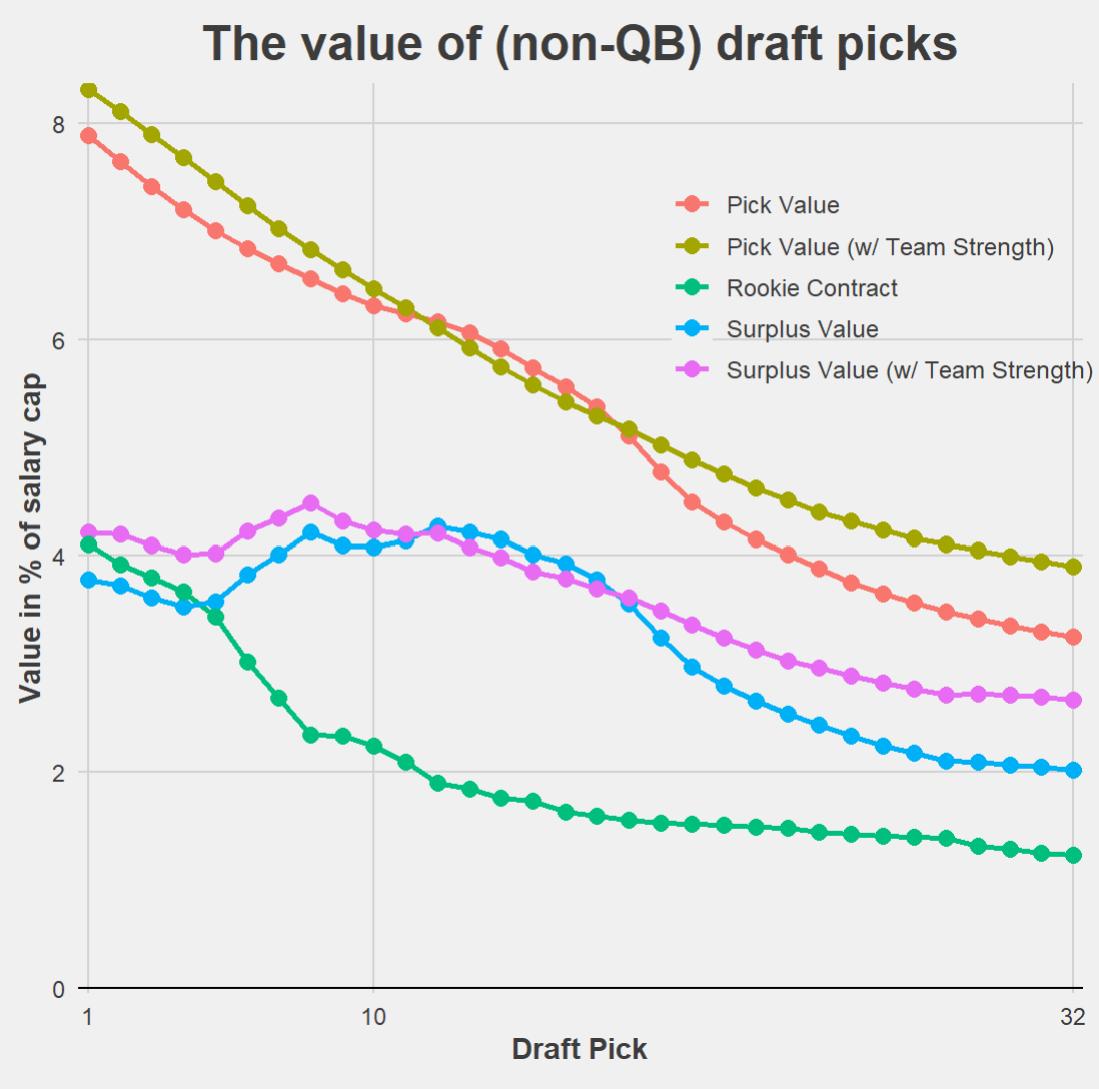

Let’s look at how this applies to the model from Baldwin’s article. Here, we use the average relative Super Bowl odds for the team strength, which comes out to a right-skewed distribution and hence is slightly positive:

This appears to support the premise of this article, that higher picks have more inherent worth than we thought, and we maybe should be less eager to rip on teams for coveting those picks because teams with higher relative odds to win the Super Bowl have been shown to do more with the higher picks than teams with weaker relative odds.

The 2011 Falcons were more likely to do more with Julio Jones than the 2011 Browns were. It’s important to note that, while higher picks have more absolute worth for better teams, they don’t necessarily have higher relative worth, meaning that the trade math won’t necessarily favor higher picks, unless one is especially coveting high-end, blue-chip talent at the very top of the draft.

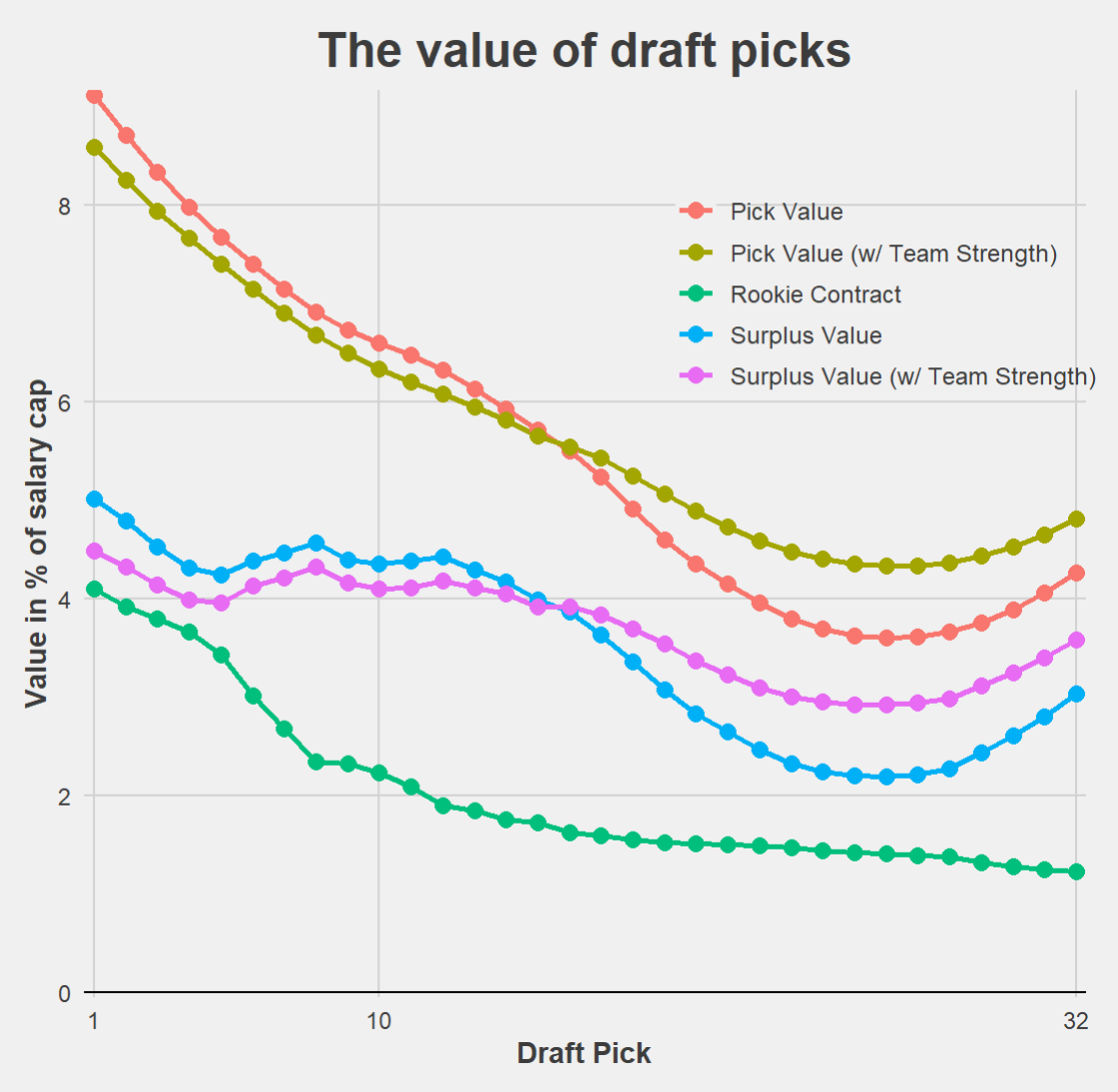

The kink in the middle of the first round, around pick 12, is notable, but it also appears in our plot that includes quarterback picks:

However, in the case of this graph, the kink around 12 is a change point, wherein it’s better to be a weaker team if you’re picking at the top of the first round if you include quarterbacks. In the back half of the first round, it is better to be taken by a better team, even at the final pick, where teams would reach back in to grab the cheap fifth-year option (on quarterbacks like Teddy Bridgewater or Lamar Jackson) prior to the 2020 CBA.

The third graph seems to dispel at least a bit of my theory at the beginning of this article, but there’s an explanatory mechanism that is rich. Firstly, the findings in the third graph coincide with those from the article I wrote a few weeks ago on sitting young quarterbacks. The generational players at the position overcome quite a bit (or they don’t, but the biggest reason they don’t is talent, not surroundings, as the team generally builds the whole plane around them anyway).

Should Rookie Quarterbacks Sit in Year One? | SumerSports

Thus, this very initial research appears to suggest that, when including quarterbacks, high picks produce more for weaker teams. I think this is because weaker teams, when picking higher, are picking at their natural spot and therefore are likely not trading away significant young assets to acquire the player.

While we suspected at the beginning of this article that support, in the form of being on a good team, was the reason we thought higher picks were worth more to better teams, it’s likely a difference in time scales: a team with great current Super Bowl chances is a great place for a non-quarterback, a position that can contribute in fractional ways early in a career, to start said career. For a quarterback, who either needs a) sustained team-building infrastructure that doesn’t rely on trading significant assets to acquire him, or b) to be transcendent, it may not be in their best interest to go to a great team picking high in the draft that traded the future to acquire them.

What I love about SumerSports, and our sports analytics community more broadly, is the ability to discuss ideas, take from one problem (Brill and Wyner’s EPA study) and apply it to another (Baldwin/Spielberger/Fitzgerald/Jimmy Johnson). We’ve known since the seminal paper of Cade Massey and Nobel Prize winner Richard Thaler’s “A Loser’s Curse”, Michael Lopez’s draft curve that considered superstar players, and PFF’s first mock draft simulator, that special exceptions needed to be made for quarterbacks, and these exceptions cannot be captured in the third graph of this article (which is one of the reasons Baldwin doesn’t include it in his article). When I was at PFF, we estimated that over the first four years of the deal, the value of the first pick was about four times more when used on a quarterback rather than on a non-quarterback.

This work, though, suggests that some exceptions should be made for non-quarterbacks as well provided your team needs high-end, blue-chip players. Good teams that covet a player may be right when they value a pick more than the charts do (aside even from individual projections of the player), as long as they acknowledge that later picks that they might be trading away are likely also going to be more valuable to better teams (this is what we found, also).

The Chiefs won the last two Super Bowls in large part because they used picks from the Tyreek Hill trade to move up to take Trent McDuffie in the 2022 draft, and he became an All-Pro and their defense became second in the league in scoring. They had 12 picks that draft and finished with 10. Depth (which they also produced in spades) was not the entire concern, getting a blue-chip player also was, and their odds of getting one at 21 were likely higher than the odds for the average team taking a player in the same spot.

NFL Draft Proverbs | SumerSports

Thanks for reading! Be sure to get your FREE 2024 SumerSports NFL Rookie Draft Guide, full of advanced tracking data and analysis for the top skill position players in the 2024 NFL Draft. For more on Draft Curves, listen to the latest episode of Stats & Scheme on the SumerSports Show Feed, available on the podcast platform of your choosing.